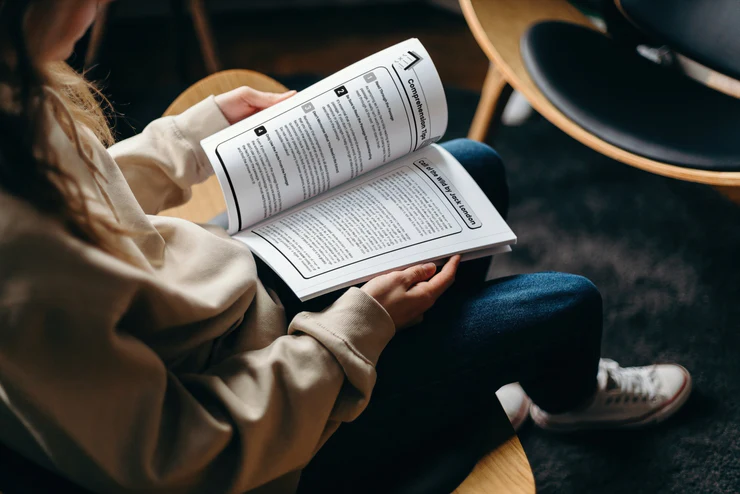

On the first day of a new job, a delivery driver’s expectations are clear: complete the route, represent the brand well, and return the vehicle in good condition. When looking at expectations in more specific situations, those expectations are no longer as clear. How should the driver behave when the route is behind schedule? How should the driver navigate in slow or heavy traffic? What should the driver prioritize when the phone keeps lighting up with updates? In last-mile delivery operations, those early pressure points are where risk starts to take shape.

Onboarding is not just an HR function in fleet-based businesses. It is a frontline risk control process. The goal of every fleet organization is to build a team and procedures that result in fewer incidents and disruptions, with cleaner claim outcomes. When management can find out more about a new driver’s skill level through early training, documentation, and accountability, it ultimately influences driver habits that hold up under real operating conditions.

Why the First Week Matters More Than the First Month

Work performance is usually measured over the first 30 days, but driving patterns form much more quickly. Within the first week, new hires recognize which parts of their route are stressful, and drivers quickly settle into their own systems and behaviors.

The most important thing a fleet manager can do in week one is reduce uncertainty. A new driver should not have to guess which matters more: speed or safety, customer satisfaction or safe parking, fast responses or focused driving. If the company does not define priorities early, drivers will define them on their own.

Day One: Set Operating Standards That Hold Up Under Pressure

Day one is not the time to overwhelm a new hire with general safety reminders. It is time to explain what safe performance looks like in this specific role. In delivery work, that usually comes down to a few decisions repeated all day.

Drivers need to hear what happens when they fall behind schedule. Are they expected to call dispatch? Are they expected to skip breaks? Are they allowed to adjust the route order? When a driver knows the approved response to delays, they are less likely to compensate by speeding or multitasking.

Day one is also where device expectations should be explicit. If the vehicle is moving, the driver should not be using a handheld phone. If a message comes in, the driver pulls over or handles it at the next stop. These rules sound basic, but without direct instruction, new hires often follow the habits they use in their personal driving.

Days Two And Three: Spot The Shortcuts Before They Stick

By day two or three, most new drivers start figuring out how to “make the route work.” They are still learning the stops, still getting used to the tech, and still trying to hit the time targets. That is when small shortcuts tend to show up, not because someone is careless, but because they are trying to keep pace.

You will often see the same patterns early on: treating quiet intersections like optional stops, creeping forward while scanning, glancing at navigation while turning, or grabbing the closest parking spot even if it creates a tighter exit. These moves feel harmless in the moment. Over a full shift, they add up, and they are usually the first signs a driver is prioritizing speed over control.

Coaching in week one works best when it gets away from vague questions. Instead of “How was your route?” ask where they lost time and what they did to recover it. Ask which stops felt awkward to park at and which stretches of the route pushed them to check their phones. Ask what part of the day felt most chaotic. You are not just collecting feedback. You are identifying where the job is nudging them toward risk.

Reinforce Reporting and Documentation Habits

By the end of the first week, drivers are deciding whether it feels safe to speak up. If a driver has a near miss, notices a recurring hazard, or experiences a close call with a pedestrian, do they report it or keep it to themselves?

Fleet organizations benefit when reporting is framed as operational feedback rather than fault. If a driver reports that one stop has poor visibility or that a driveway forces an awkward reverse, that information helps with route and safety planning.

Documentation also matters in week one because it establishes consistency. When training, expectations, and coaching are documented from the beginning, accountability becomes clearer. It also supports the company if an incident is later reviewed by insurance or legal teams.

Priorities: What the Company Should Make Non-Negotiable

If your onboarding process only has room for a few non-negotiables in week one, focus on the items that drive the most preventable incidents.

One is speed management. New drivers should understand that speeding to catch up is not viewed as good performance. Another is device discipline. If drivers are required to stop before interacting with handheld tools, that rule has to be consistent across supervisors and routes. A third is parking and backing standards. Delivery work includes constant maneuvering, and that is where many incidents happen.

Week one is also when managers should clarify what drivers should do when they are behind. When that process is clear, drivers are less likely to make risky decisions to recover time.

Conclusion

The first week behind the wheel is when delivery drivers learn what the company truly values. Policies matter, but what happens during week one is what shapes habits. Clear standards on speed, devices, parking, and reporting remove guesswork when the day gets hectic. When management can find out more about a driver’s skill level through early coaching and documentation, they can correct patterns before they become incidents. Over time, that week one discipline leads to fewer disruptions, stronger accountability, and fleet operations that run more consistently.